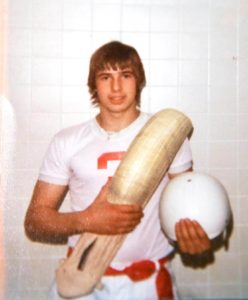

Associate Spotlight: From Jai Alai Court to Assisted Living Community

Longtime Blenheim-Newport associate reflects on

two very different but rewarding careers

When Miguel Amoros began working at Blenheim-Newport in 1994, residents would occasionally give him a double-take as they tried to place his face.

The lucky few satisfied their curiosity and finally asked Miguel – much to his delight.

Miguel had been a professional Jai Alai player for two decades in Newport, Rhode Island. The surrounding community of Aquidneck Island had embraced the fast-paced sport and the wagering that went with it.

“Some of the residents would tell me, ‘I used to win with you all the time,’” said Miguel. “Of course, I didn’t win all the time. They would say this to make me feel good. That’s one of the reasons I love the residents so much.”

When Miguel’s Jai Alai career neared the end, he wanted to settle in Rhode Island to raise his three children and be closer to his wife’s family. Enter Blenheim-Newport. For the last 27 years, Miguel has taken care of the community’s building and grounds, among other responsibilities.

“Miguel is one of the most popular of associates. They love him,” says Sharon O’Sullivan, Executive Director of Blenheim-Newport.

A Dream Come True

A Dream Come True

Like other boys raised in the Basque Country of Spain, Miguel dreamed of joining the ranks of the great pelotaris – the Jai Alai players who traveled the world to compete in and share their region’s unique sport.

“My town, Markina, was the universe of Jai Alai. We all wanted to be like the professionals,” he said. Miguel remembers successful players returned to his town from various parts of the globe, driving fancy cars and drawing admiring crowds.

While Miguel started playing the sport at a late age, 14, he quickly got noticed. He would spend countless hours at a cancha, the court the sport is played on, honing his skills catching the small hard ball in the basket-like cesta and slinging it against the three walls of the court, with the goal of making his shots difficult for opponents to catch and return.

At age 16, his dream came true. Miguel signed a two-year contract with MGM to play in Reno, Nevada. At the time, Jai Alai was growing in popularity in the United States as a gambling alternative to horse and greyhound racing.

When his contract ended with MGM, Miguel signed with another company to play in West Palm Beach during the winter and in Newport during the summer.

Quick and athletic, Miguel soon established himself.

“You need to be fast and have good reflexes,” he explains, noting the ball travels between 150-160 miles per hour. “Most of all, you need to figure out how to make the point.”

Miguel says he earned good money and enjoyed the two U.S. cities and surrounding area and the life of a professional athlete. But it was hard work and required training to stay in shape and competitive.

“It could be stressful. It’s up to you to win games and make sure you don’t stink, if you want to keep playing,” he said.

Turning the Page

Before Miguel knew it, 20 years of competition and travel had passed. Meanwhile, he had a wife, Elizabeth, who he met when she was selling tickets at Newport Grand Jai Alai. He soon had children to support as well. At 36, a new career was inevitable, especially as the sport’s popularity began to slip.

It was Blenheim-Newport that came to him. Miguel had worked at the community in the early 1990s when Jai Alai players went on strike for three years. The community wanted him back.

“At the time, I was in West Palm Beach. When I got the offer to come back, I did. I’m glad I did,” he said.

Miguel has always felt at home in the community. Residents enjoy the gentleman’s kind smile, his wisecracking and the time he takes to ask them how they are doing.

“And when I solve a problem for them? Well, you see on their faces the gratitude. Something very small is big to them,” he said. “It is such a great feeling for me to see them happy and smiling.”

A Sport, Tradition in Decline

A Sport, Tradition in Decline

In early June, Miguel was preparing for a two-week visit to his hometown in Spain. It had been two years since his last trip due to COVID-19 travel restrictions.

He was looking forward to seeing his brother and sister and their families, and catching up with former Jai Alai players and friends in the region. Of course, Miguel was eager to watch as much Jai Alai as possible, as he is unsure of its future.

“It’s sad because the sport is kind of dying,” said Miguel, who is now 60. He pointed out that a few years after his retirement, Jai Alai folded in Newport – giving way to slot machines and other gaming. The number of frondons, the buildings that house Jai Alai, are a fraction of what it used to be in the United States and worldwide.

And while he’s disappointed to see the game fade, Miguel remains grateful for the experience.

“This was a sport that 60 to 75 percent of kids where I came from wanted to play. It’s not like that anymore,” he explained. “I wish they had the opportunity to do what I did. It’s such a beautiful sport.”

Blenheim-Newport