Who We Are – Rising Above Segregation

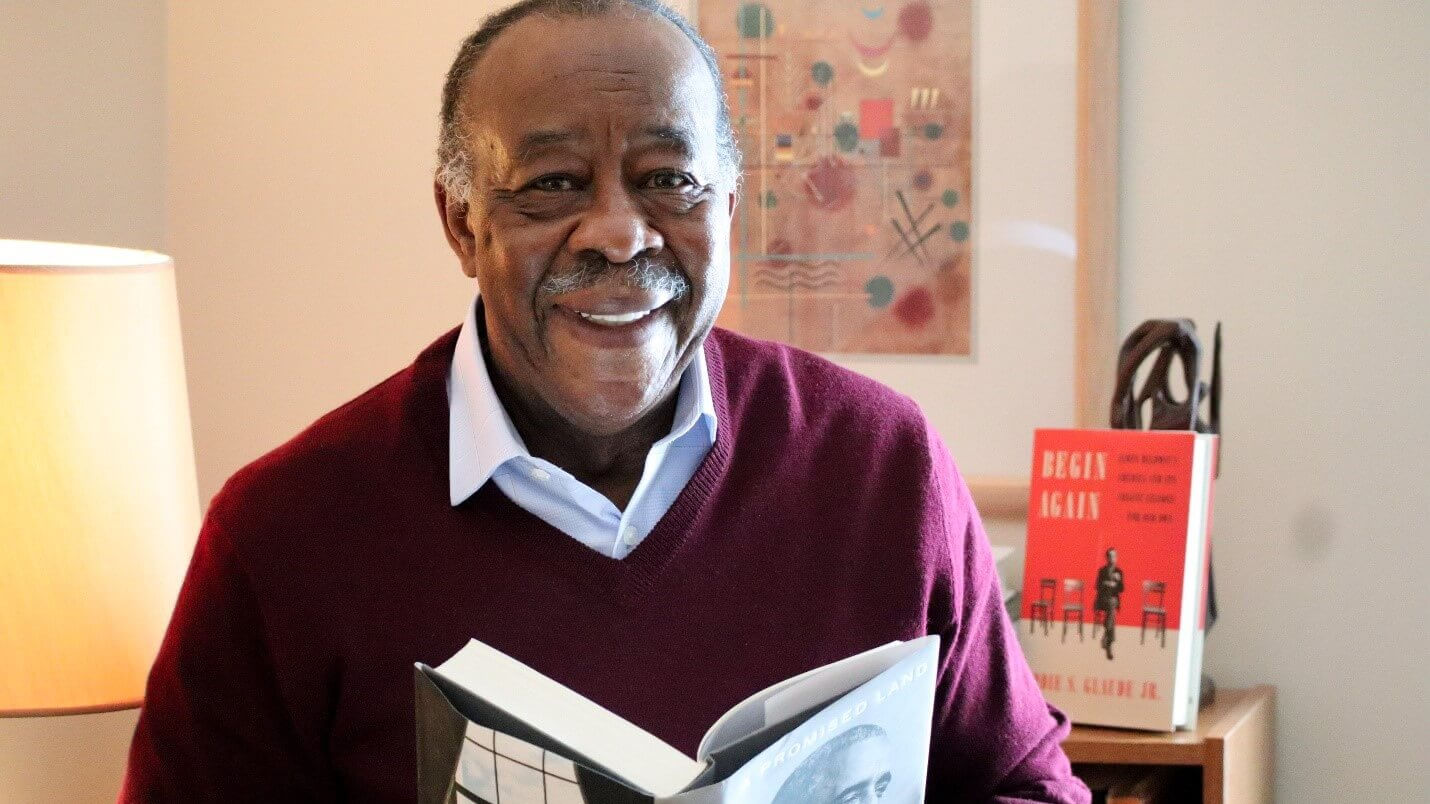

Cabot Park Village resident has fought for the rights of all

Lionel Porter knows firsthand what it’s like to experience segregation. He can still feel the aura of fear that surrounded and shaped his early childhood in Canton, Mississippi.

“While walking to church one day, we saw blood on the street because a black man had run from a white police officer. To warn all of us what could happen if we didn’t behave, the blood was left there as a constant reminder,” said Lionel.

The message was received, white people were to be stayed clear of, he said. Even a routine traffic stop by a white police officer was cause for the entire car to tense up and receive a stern warning from his mother.

It’s these early beginnings that helped Lionel form a lifelong desire to fight for people like him who experienced discrimination.

Parents Sacrificed for Their Children

Lionel, a resident of Cabot Park Village, is a descendent of slaves. His family history in Canton dates to around the 1830s when it was settled as an early cotton farming center. His great grandfather was a proud sharecropper who constantly battled against being cheated by his landowner. In 1862, Canton had a confederate branch and today many monuments exist there that commemorate slaves who were lost during the Civil War.

Concerned about the poor education at Canton’s segregated public schools, Lionel’s parents had the foresight to send him to a private school for Black students, Holy Child Jesus School. Lionel attended school alongside Thea Bowman, who would later become a nun, well-known writer, educator and activist for cultural awareness and racial harmony.

Wanting their family to have full citizenship and finally be landowners, in 1950, Lionel’s parents and their eight children were among the over 5,000,000 African Americans who migrated to Indianapolis during the Second Great Migration.

A New Beginning

In the Southside of Indianapolis, the family was embraced by others who had experienced persecution, mainly Sephardic Jews from Europe and other African Americans who had immigrated from the south. They adjusted seamlessly, and the better life they longed for had finally become a reality. They bought a home in an area where no one locked their doors at night. His father got a job on the railroad, and his mother stayed home to care for their large family.

Despite the racism they had experienced in the south, his parents raised him to be open to everyone. “They never talked negatively about anyone. We were neighbors with and played with kids from all walks of life. It was an idyllic childhood. We felt like we were in a cocoon,” Lionel said.

With the strong support of his parents and others in the community who inspired and guided him, Lionel worked hard. While the school assumed his southern education would be a setback, Lionel excelled. He was the best reader in his class, became the annual spelling bee champ at his grade school, the first city wrestling winner in his family and got a part-time job at a Jewish bakery. He was eventually awarded a partial college scholarship for wrestling and continued to wrestle while pursuing an English degree with the goal of being a teacher.

While his formative years were idyllic, Lionel never forgot his early experiences in Canton. He continued to have a burning desire to become a lawyer so he could fight for those who were less fortunate and defend “the rule of the right,” but always talked himself out of it. “After I graduated, I remember grabbing a law school application and later throwing it away,” he said.

After earning his bachelor’s degree, he taught high school. Later, he transitioned to the insurance industry for more opportunities and a better income. He eventually relocated to Connecticut so he could work for Aetna. In 1971, he and his wife began visiting Boston annually where he enjoyed seeing jazz greats Freddie Hubbard and Rahsaan Roland Kirk as well as Peaches & Herb perform.

Fighting for What’s Right

It wasn’t until 1981, when working for the University of Connecticut Health Center’s Affirmative Action office that Lionel could no longer deny his legal calling. He went to law school at night and eventually earned his Juris Doctorate degree.

Over the last 36 years, Lionel has finally been able to do what he’s always dreamed of — fighting for those who experienced discrimination like he once did. He’s served as Legal Redress Chair for a Massachusetts branch of the NAACP and worked in Connecticut and Massachusetts to mediate employee discrimination cases.

In 1994, while working in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island he found there was a growing backlog of discrimination complaints. For the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities’ to simply assign a complaint to an investigator could take a year, he said. He worked to develop a dispute resolution system to be used by the rights commissions to speed the process.

In Connecticut, that same year, House Bill No. 5605, an act allowing the human rights agency to recommend alternative dispute resolution to complainants was passed to help speed up the process.

“It’s been incredibly gratifying to help those who have been discriminated against purely because of their age, gender or skin color,” said Lionel.

Pursuing Passions at Cabot Park

Today, Lionel is enjoying life at Cabot Park Village, a Benchmark independent living community in Newtonville, Mass.

He enjoys being within reach of Boston’s many educational and cultural opportunities. He appreciates the diversity amongst the community’s residents, many of whom are Jewish, and the diverse associates, especially the servers, who hail from places like Peru and Portugal who, he says, “deliver service with such pride.”

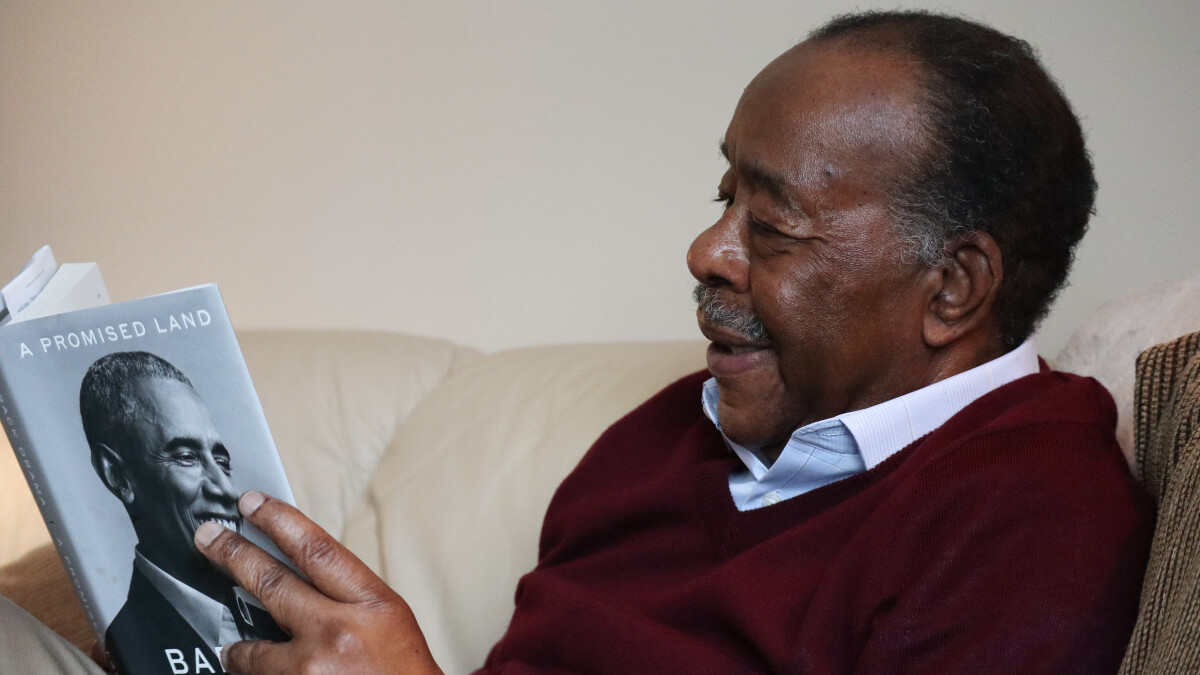

Every February, Lionel leads the community’s Black History Month lecture series, an extension of his passion for researching and preserving African American history. Two to three times a week, he produces and leads lectures on topics like notable black writers, white supremacy, and reconstruction.

“I have many friends here and enjoy living in a community where I can share in what I love with like-minded people,” he said.

Even at 78, Lionel says his work is far from over. He’s looking forward to starting his own law practice soon so that he can share his expertise and help others.

“I feel like I still have so much to share, and with what’s happening in the world right now, the need is great,” he said.

See a WFXT, Boston 25 story about Lionel here.

For more Black History Month stories and interviews from our residents and associates, please visit pages below:

• Tashara Leaky’s Story

• Dr. Dorothy Pieniadz’s Story

• Johnnie Mae Foxworth Becomes a Centenarian

Cabot Park Village